Every time we go to the movies, we are reminded to be terrified of alien life. Whether they are blowing up national monuments, demonstrating unimaginable power over us, or eradicating us like pests, the world of cinema makes it very clear that aliens are things to be feared. Stephen Hawking had famously warned us against contact with alien life, fearful of our colonial history repeating itself on a planetary scale. But what kinds of aliens are we most likely to find? And what implications would those life forms have for the scientific community?

Life has been around on Earth for about 3.5 billion years – an incredible amount of time on the human scale. For the first 2.9 billion years of that time, all life was confined to single celled organisms, the bacteria and amoebas that still cover the planet.

Imagine that for a moment: from the first cell taking shape in Earth’s oceans to you reading this sentence – for more than 80% of that time life had not become complex enough to become multicellular. That leap from being one cell to two is quite a large one, and it’s possible that there are countless planets out there with life that never made that leap. From looking only the example of our own world, we could suppose that if we do encounter life at all in the cosmos, there is a very good chance that these life forms will be tiny.

Taking this in to account, should we still fear these alien bacteria? We may not be facing the enemies suggested by Hollywood’s Mars Attacks or Men in Black – little men armed and ready to destroy – but with the discovery of an alien microbe, should we be fearful?

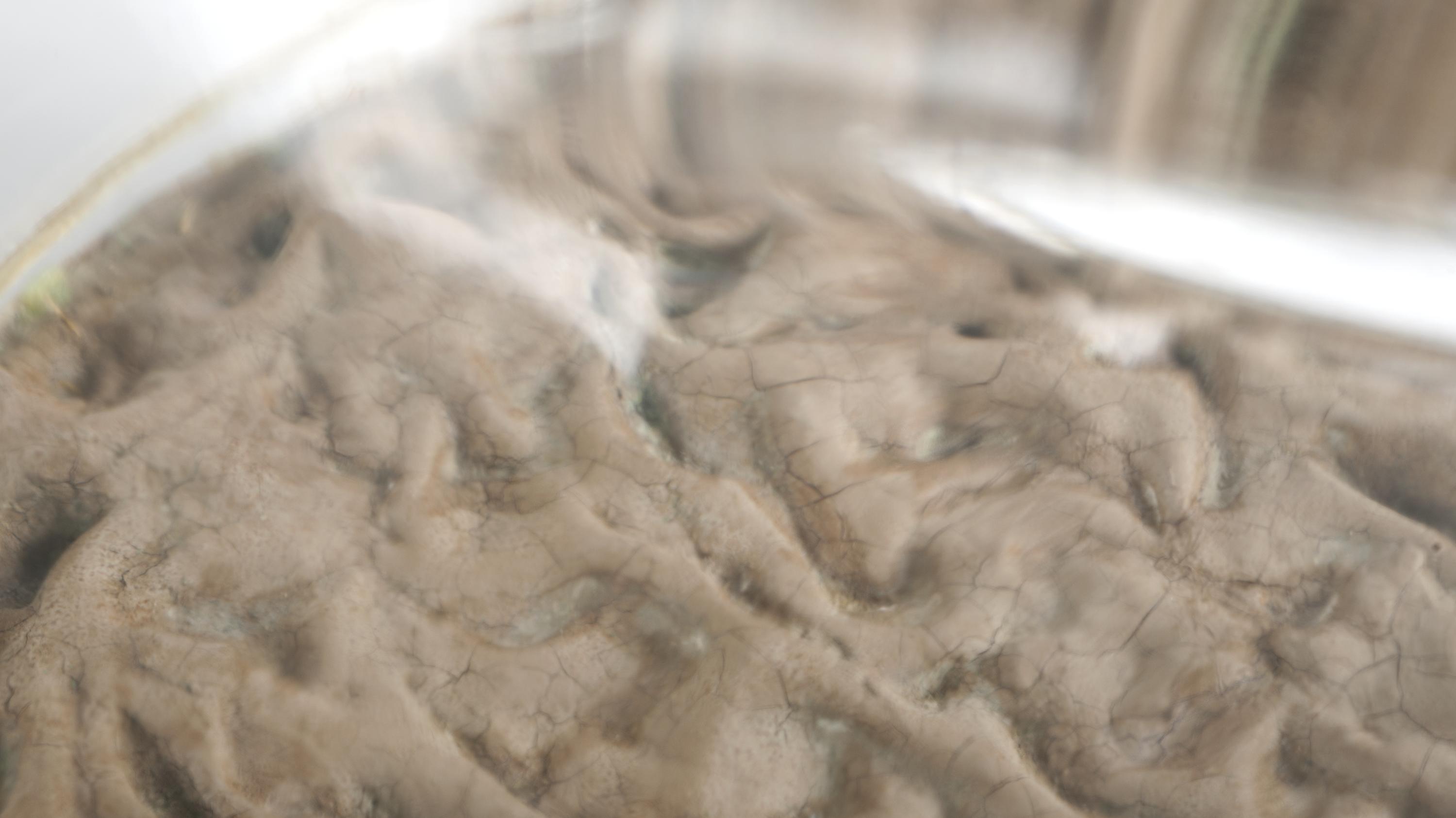

We like to think of us humans as being the dominant species on Earth, but truly, it is bacteria that are able to adapt and thrive to any environment, whether they are bombarded with radiation, faced with extreme heat, or put under great amounts of pressure. If we ignore viruses – which may or may not be considered alive – bacteria are the most prolific living thing on Earth. By all accounts, we are living on their planet.

Our bodies, too, are an ecosystem dominated by bacteria. Recent studies have shown that about 43% of cells in our bodies are human, with just over half of our cells being bacterial. Because we have evolved alongside these creatures, our bodies are already equipped to deal with harmful infections and the presence of bacteria is thought to support the different systems within us.

These bacteria are incredible creatures, capable of swapping their DNA with one another, multiplying quickly to mutate and develop, and living lives in our gut that we would otherwise associate with something like a lion on the savannah: hunting, eating, forming communities, producing offspring, working as a team with others to gain access to resources. Their ability to share genetic code and reproduce is what is driving our problem of antibiotic resistance today – bacteria can evolve much faster than we can invent new medications to get rid of the bugs that are causing us harm.

Now let’s suppose a new microbe enters the mix. Let’s say, something brought back on a mission from Europa – something that our bodies have never seen before. Chances are, like with most bacteria, it would sit harmlessly in our system until it died, was attacked by our other bacteria, or noticed by our immune system and wiped out. But there is also a possibility that this new life form could interact with our bodies and with other bacteria in completely unexpected ways.

For example, if these aliens were to have extra thick cellular walls, they would be much more difficult to kill by either our immune systems or antibiotics. While these bacteria may be completely harmless to us, other bacteria can still exchange DNA with it, empowering other organisms within our bodies to also grow this thick shell.

Bacteria love to share, and the more they share their defences, the harder they are to kill. Given time, you would be full of microbes with this alien DNA that made any infection you would pick up resistant to medicines and to our natural defences. This is, of course, assuming alien bacteria would have similar biology to what we have here on Earth, being carbon based and complete with DNA. Finding something completely foreign could be potentially disastrous, creating disease or systemic infection to which there would be no known defence.

At the same time, finding a new alien microbe could open new doors in the medical world. Many of our antibiotics are derived from nature – moulds and bacteria fighting one another – that we have in turn manipulated to fight infection on our behalf. Streptomyces, an example of a bacterium that lives in soil, has given us many antibiotics. But with the rise of antibiotic resistance and the emergence of superbugs here on Earth, we need new microscopic weapons to use against diseases that are becoming increasingly difficult to treat, like gonorrhoea or tuberculosis.

A new species of bacteria – something we’ve never seen before – could give us that weapon that we wouldn’t find anywhere on Earth. A new species could mean new medicines to protect us and future generations from infections.

Despite some false alarms, we’ve never found evidence of alien microbes and such a discovery would change our place in the universe forever. While we’re most likely to find microscopic life on our interplanetary adventures, we could either be facing a great danger or potentially the key to incredible progress.

Much like the stories we see in the movies, we won’t know what this kind of contact will really mean until it’s here.

Visit our free exhibition Superbugs: The Fight for Our Lives to see real bacteria and discover the innovative technologies being used to develop new antibiotics. Open until Spring 2019.