After a hugely popular run at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, Turn It Up: The power of music arrived at the Science Museum in London this autumn. This interactive exhibition explores the mysterious power that music holds over us as well as displaying weird and wonderful instruments. But before going on display, these objects were in the careful hands of our conservators who prepared them for their moment in the limelight.

Conservators Julie McBain and Diana Hepworth look into the care given to two objects which have been part of Turn It Up, and look back on their meticulous work to restore a metronome, a glass harmonica, and even a pyrophone – an organ powered by flames.

The Glass Harmonica by Julie McBain, Former Conservator at the Science Museum

When I started work in the conservation department , I was handed an object list for Turn It Up: The power of music. What an amazing adventure I was about to embark on.

At that point I had no idea what a chocolate phonograph, a glass harmonica or a chladni plate (which you can see in action here) were, and I certainly didn’t know what they sounded like. Whilst undertaking practical work, I would search for the object I was working on and inevitably I’d find a short film demonstrating the sound of each instrument or lectures explaining the physics behind the object.

Most of the objects had historically been kept in a poor environment and they were thickly covered with black residues. This was not how the objects would have looked in their heyday of use – they would have been objects of pride. They had to be cleaned: being so dirty is not good for any material as the carbon residue can absorb water from the atmosphere creating a weakly acidic environment.

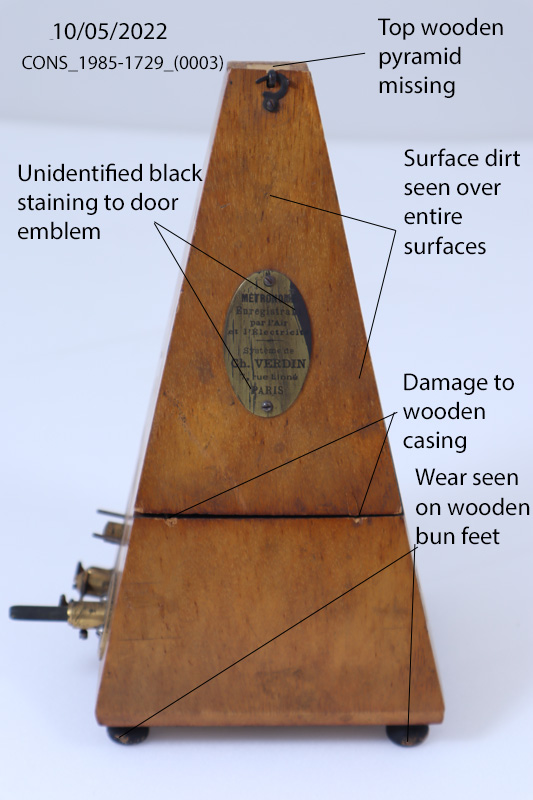

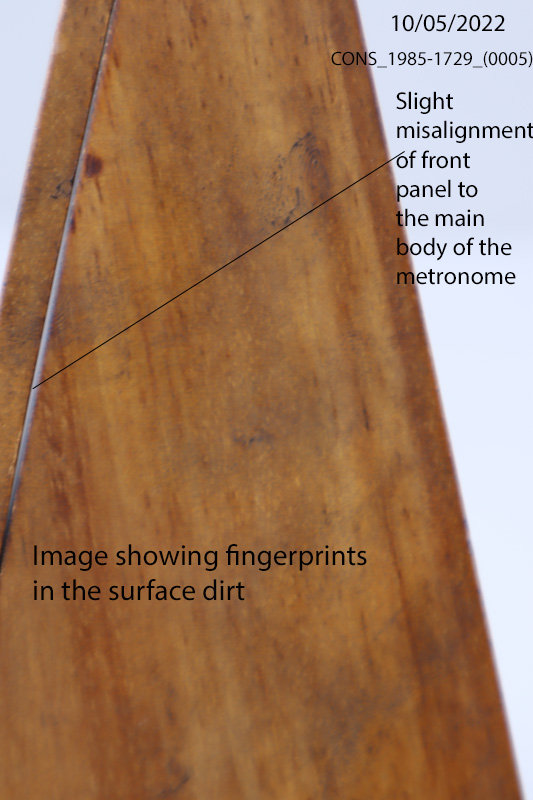

A metronome was one of the first objects I chose to work on. I felt that it would be a simple job, one that would ease me in gently. But, then again, I hadn’t really expected any objects to be as dirty as the metronome. There were thick black fingerprints on the wooden casing and what looked like a black ink streak on the manufacturer’s emblem attached to the front panel. I had visions of a musician sitting at their piano, an ink pot and quill in hand, composing and writing whilst keeping time with the ticking metronome, inky fingers stopping, starting, and recalibrating the beat.

My imagination had run wild and upon closer inspection the black fingerprints were just from poor historical handling of the object. While I felt disappointed that I didn’t get the chance to preserve the fingerprints of the anonymous musician I had pictured, the cleaned metronome is now in a more stable condition which can be enjoyed by generations to come.

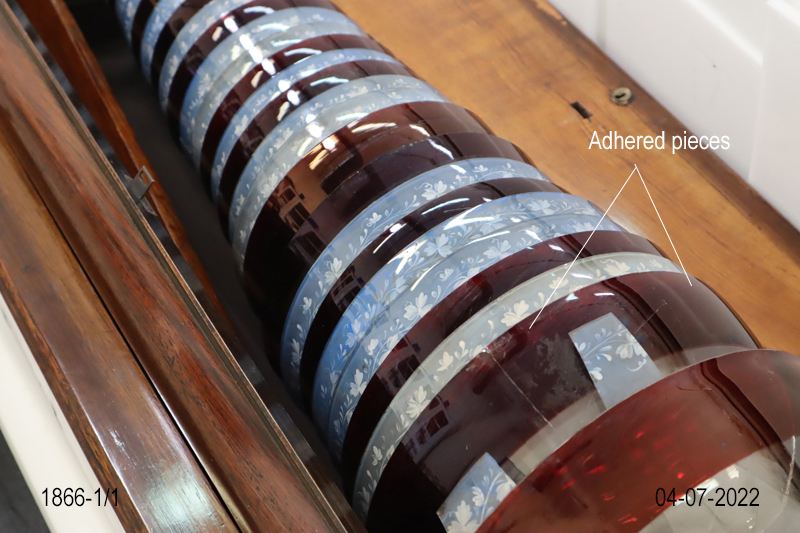

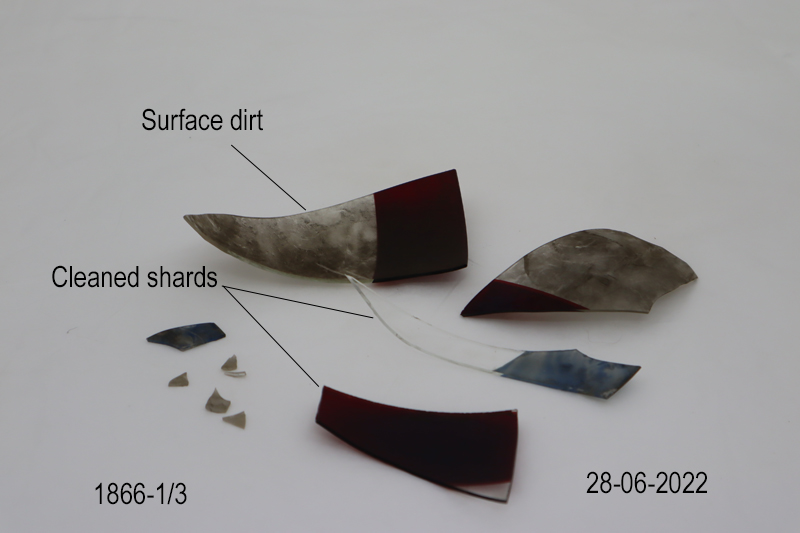

The glass harmonica was the object that I kept till last: I must admit I was a little scared of conserving this item. In addition to its fragile glass material, it was big and heavy, making it particularly tricky to work on. . It turned out to be a delight. With the help of some colleagues, it was moved to the lab where work could commence. There were five large fragments which had broken off from the rest of the instrument.

Three pieces fit together and the other two slotted together perfectly. When the fragments had been put together with a conservation adhesive and left to cure, the task of matching them to the broken glass bowls of the harmonica could be undertaken. Much to my delight, the adhered fragments fit perfectly into two of the broken bowls.

It’s a delight to work on historic objects but even more delightful when they make beautiful music: you can listen to the glass harmonica in action in this video.

Conserving and packing the Pyrophone by Diana Hepworth, Conservator at the Science and Industry Museum

Turn It Up: The power of music opened my mind up to a new realm of musical innovation where an egg slicer can be plucked to make electronic tunes and melting ice can produce a shifting symphony of sound. Among these fascinating objects was the pyrophone, which played music by shooting fire up a series of glass tubes. Unfortunately for the visitors (but thankfully for me), you cannot see the object in action, but a video playing next to it demonstrates the unique sounds triggered by the fire, reminiscent of an old steam ‘choo choo’ train.

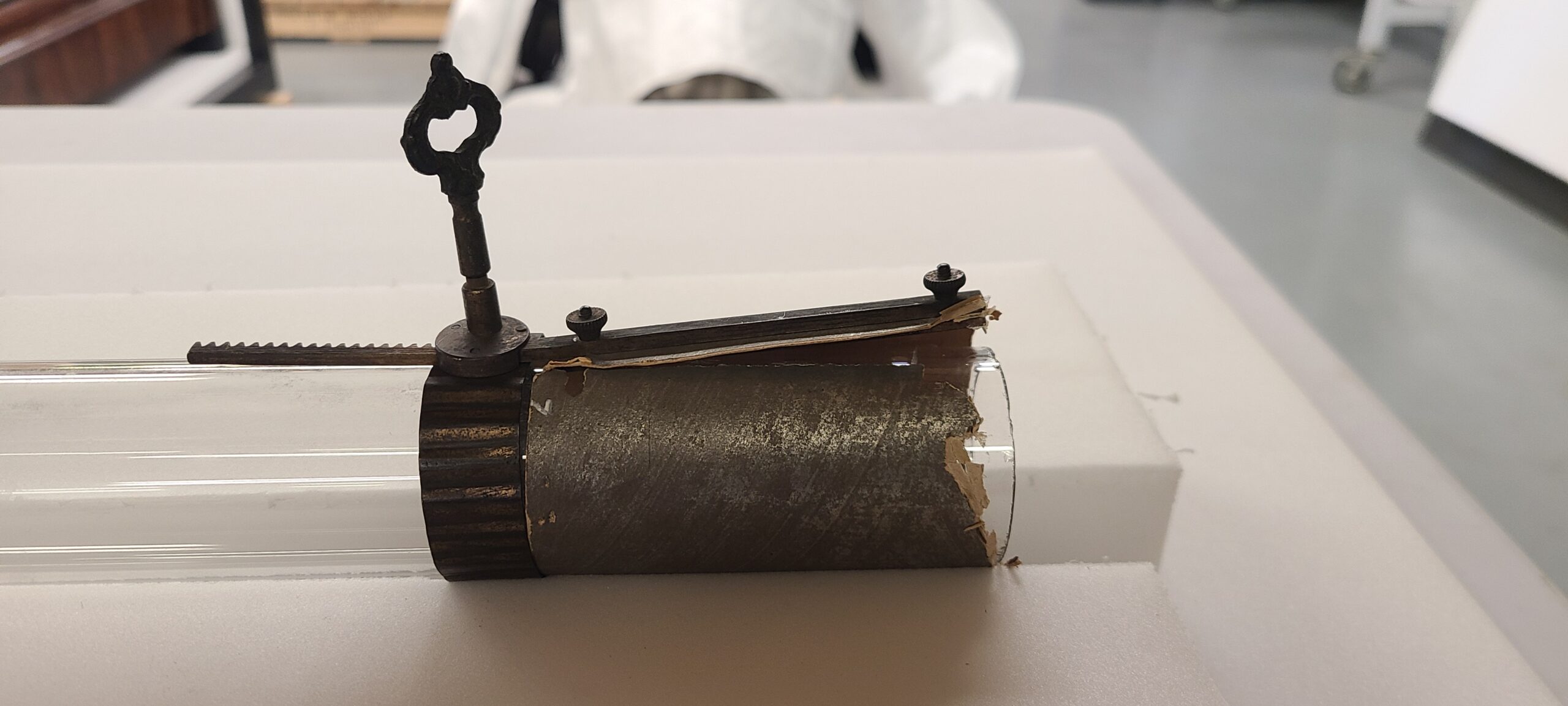

This beautiful object also brought me the biggest challenge when it came to conservation as some of glass tubes were unfortunately damaged. The most significant damage was to a metal bracket that held a delicate paper tube in place. The bracket had bent back to a 90-degree angle and ripped the paper from the glass tube.

When it came to getting the pyrophone ready for its install at the Science Museum, I carried out extensive conservation to ensure it would be stable enough for transport. This involved rejoining and reinforcing the ripped paper and colour-blending to hide the repair.

Once the conservation was complete, our team packed the glass tubes and pyrophone body into two separate crates. The thirteen tubes being the most delicate components were individually fitted into numbered foam slots. The fire rods were also very delicate and the bulbs that shot fire were brittle and prone to break off with any excessive vibrations. Therefore, each rod had to be padded and secured to minimise vibrations during transport.

Though the journey of the pyrophone was a time-consuming process, it was satisfying to see that it made it all the way to London and can be enjoyed by many more visitors to come!