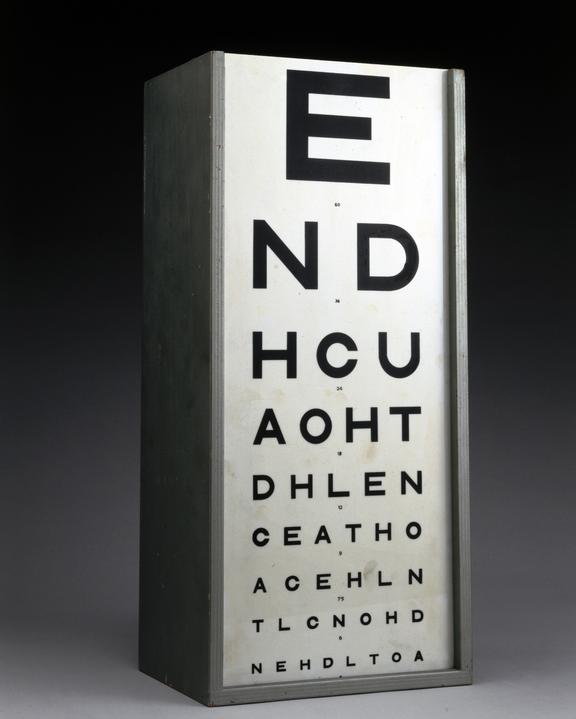

As expected, the year 2020 has presented the opportunity for attention-grabbing puns relating to vision. The term ’20-20 vision’ is used in ophthalmological circles to express visual acuity, a person with perfect vision can read an eye-test chart from a distance of 20 feet.

However, metaphorically, the phrase has come to mean having focus and clarity but this meaning is often regarded as offensive and “ableist” to people with visual impairment.

It was this, the recently renewed gratitude for the NHS and the anniversary of its creation that led me to reflect on how my historical research on NHS glasses has inspired my current mission to support innovation in disability-related design.

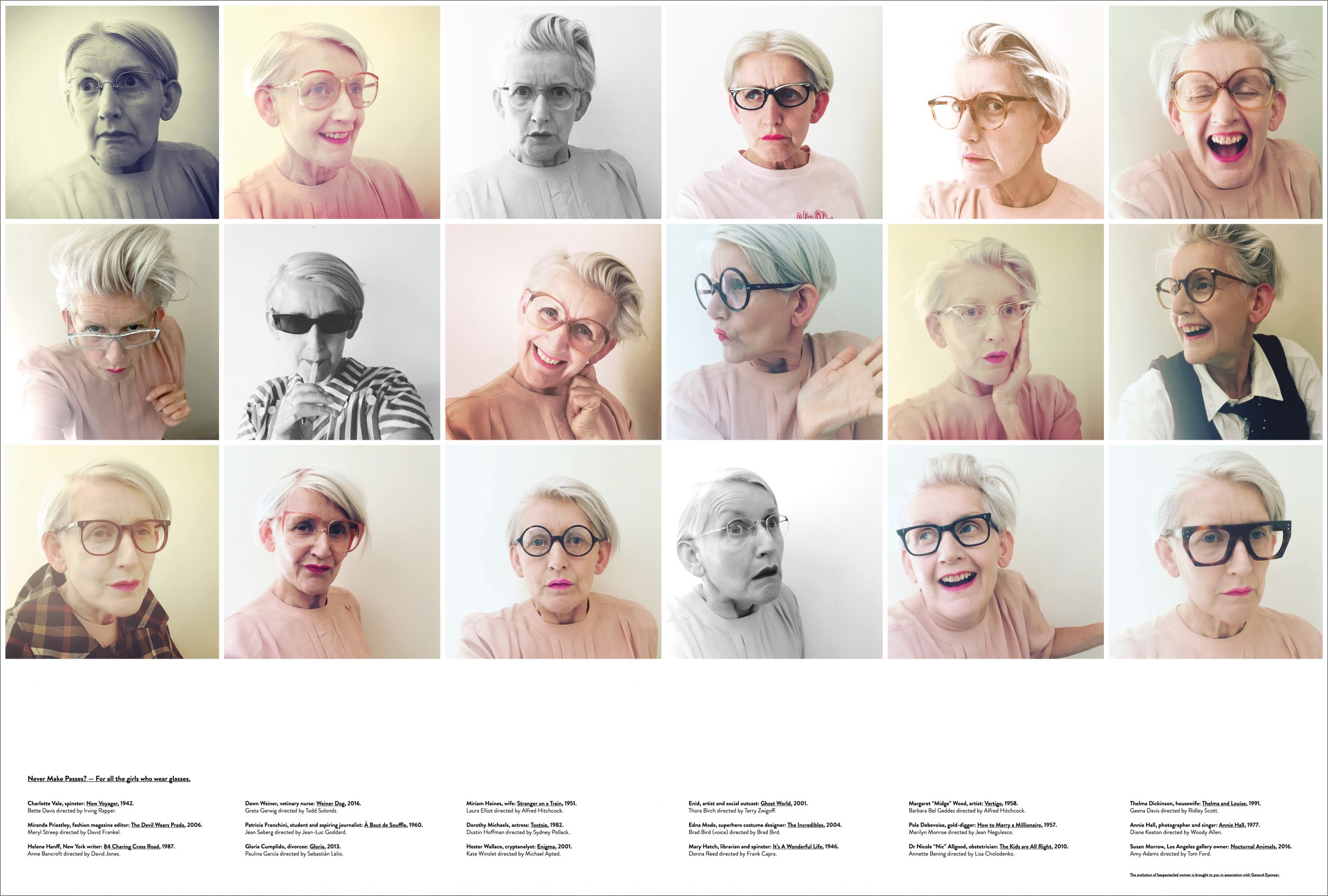

I have always believed in the power of objects to convey meaning and to elicit memory and this happened at a talk I gave to the Costume Society back in 2017. After discussing how the reputation of NHS glasses had evolved from a much-despised medical appliance to a retro fashion accessory a lady shared a personal anecdote with me. She had worn NHS glasses as a child but her mother had insisted she removed her spectacles before leaving the house so that the neighbours did not see. The style of the frames was so recognisable as state-supplied spectacles that they had evolved into so-called ‘badges of poverty‘.

A factor that contributed to this social stigma was there were only a few styles available and those hadn’t been updated in forty years. This meant that individuals had little to no choice and therefore little opportunity to express their identity and personal style. For those who could not afford an alternative, this stigma had a lasting effect.

In 1985, when the ophthalmic industry changed as an NHS voucher system was introduced, there was an opportunity for choice, and this relationship certainly changed. Now, younger generations wear vintage NHS frames as a way of expressing their style.

In disability-related design, glasses are cited as an example to be aspired to. Spectacles have evolved from a stigmatised corrective appliance that is dispensed in a clinical setting into a trendy fashion statement, with frames sold in retail stores and boutiques.

Other devices such as walking aids, orthotics, and prosthetics, can learn from this when thinking about design. As we’ve learnt from the past, design is hugely important and can have an impact far beyond its practicality, function, and aesthetic appearance.

So, to join the cliché I mentioned earlier, my vision for 2020 has certainly been re-framed from simply documenting the history of eyewear to exploring how to use the lessons learnt to support innovation in inclusive design.

Once the Science Museum has re-opened you can see more pairs of NHS glasses on display in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries but in the meantime, we encourage you to explore our online collection.

One comment on “Re-framing my vision for 2020”

Comments are closed.

I was prescribed my first pair of NHS specs when I was 10. They weren’t pretty. I looked like my auntie. I also looked like famous people such as Joe 90, as my then teacher was happy to point out. Two years later the rules changed and my options opened up a bit more. My new frames were blue, it was a real gamechanger.