2 May 2019 is the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci.

Da Vinci was born near Florence, Italy, in 1452 and died in 1519. He has a reputation as a painter of the Mona Lisa in Paris, and The Last Supper in Milan – two of the most recognisable images in the world.

However, he was also an engineer, anatomist, architect, sculptor and much else besides.

He was the ultimate ‘Universal Man’, able to master a superhuman range of subjects.

Da Vinci recorded his work using a new visual language.

His notebooks contain a remarkable mixture of drawings, sketches, fragments of thoughts, workings and new ideas.

Often he used mirror writing working from right to left, which he could do easily being left-handed.

Together his notebooks have been described as a ‘visual laboratory’, and they have inspired many to try and recreate his ideas, including the Science Museum.

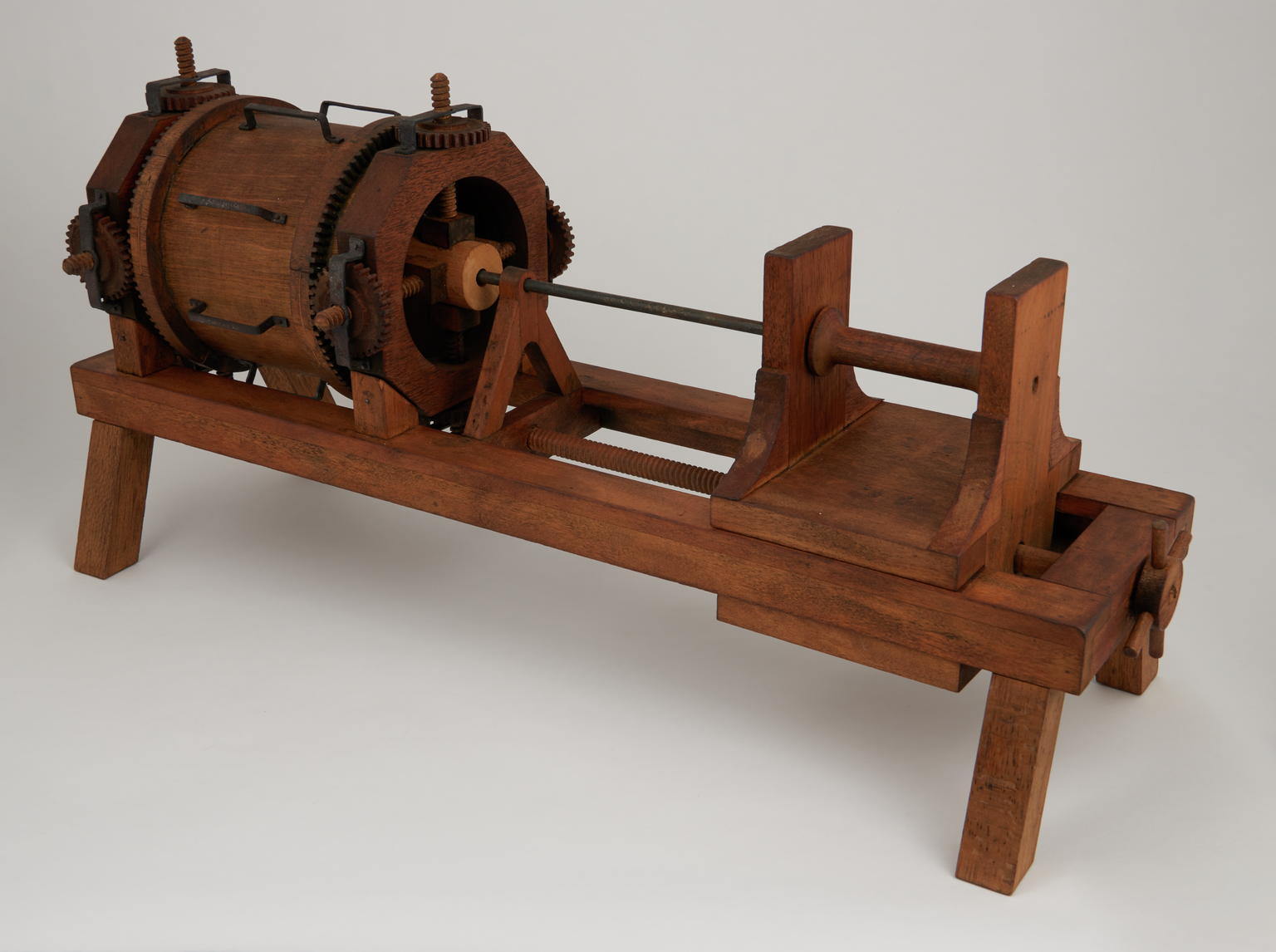

Our collection has a range of models giving physical form to some of da Vinci’s ideas.

One of his aeronautical interests was sketching ‘ornithopters’, flying machines that depended on flapping wings to operate, just as birds’ wings allow them to fly.

His sketches were made in 1486-90. In 1929 the museum commissioned two models showing how they might have worked in practice.

They were accompanied by a model of Leonardo’s idea for a parachute.

If this looks impractical, adventurer Adrian Nicholas built a full-scale version of it in 2000, and in jumping out of a balloon found that it worked well, giving a smoother ride down than a more conventional parachute.

Later, in the early 1950s, the museum commissioned a further set of model machines conceptualised by da Vinci towards the end of his life: a helicopter, and machines for cutting screws and metal-working files, boring pipes and grinding mirrors.

It may be that some of da Vinci’s ideas could not have worked in his lifetime, particularly his flying machines. He may have out-paced developments in materials and technology that could have made his ideas a reality.

But, da Vinci’s ideas and models remain as vivid reminders of the value of curiosity, of exploring, thinking laterally, and building bridges between art and innovation.

Hang on to your sketchbooks, perhaps one day they will be of equal interest to historians, engineers and artists.