The Science Museum’s latest blockbuster exhibition, Robots, was unveiled yesterday in the Science Museum, revealing the most significant collection of humanoid robots ever displayed in one place.

A twitching animatronic baby; a 16th-century mechanical monk that beats his breast in contrition; a restored replica of Eric, the UK’s first robot; Baxter, which can draw on a global hive mind; and a small band of research ‘bots were among more than 100 machines that star in Robots.

Through the dazzling medium of robots, the exhibition explores how religious belief, the industrial revolution and popular culture have shaped society over half a millennium, inviting visitors to dream what a shared future with robots would be like.

At the press launch for 170 journalists, Ian Blatchford, Director of the Science Museum Group, said: ‘As a mirror for humanity, robots offer deep insights into our changing hopes, fears and dreams.‘

The exhibition, which trended on Twitter, was given four stars by The Daily Telegraph, which refers to the ‘mind-bending array of humanoid imagery.’ The Guardian describes the ‘trove of robotic delights’ and the Times calls it a ‘bold and compelling show.’

BBC Breakfast broadcast live from the exhibition to approximately six million viewers, approaching 200,000 watched BBC News’ Facebook Live and first of three BBC Radio 4 programmes entitled ‘Rise of the Robots’ aired yesterday morning. The event became global news, thanks to Reuters, Al Jazeera, CNN, USA Today, Wired, The Hindu and Xinhua News Agency.

At the evening VIP event, the Philharmonia played Things to Come, composed by Sir Arthur Bliss for the 1936 science fiction film of the same name, which gave H. G. Wells’ vision of the world until 2054.

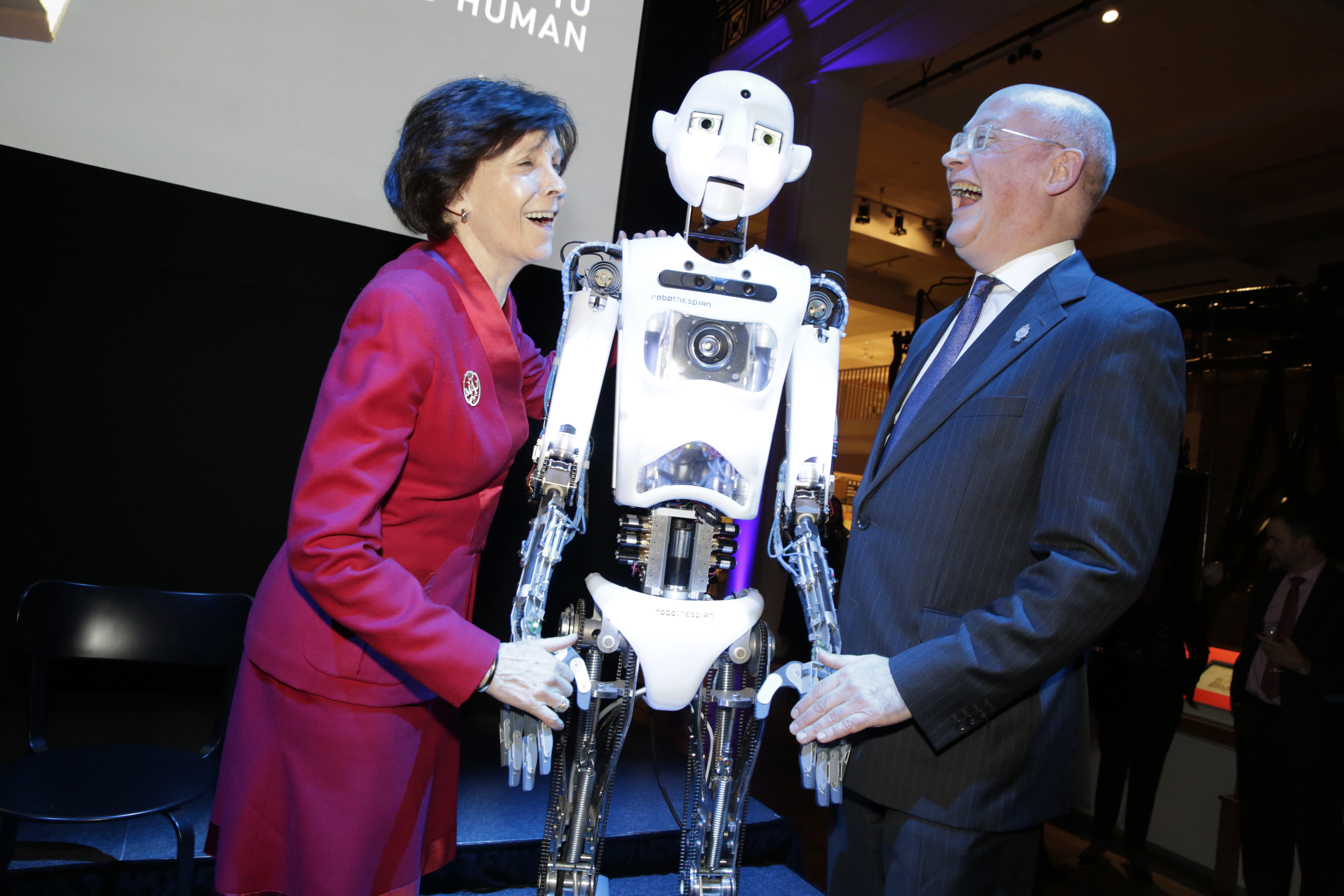

The orchestra’s ‘semiconductor’ was RoboThespian, developed by Engineered Arts, who implored the throng of 500 VIPs to ‘strike the palms of one’s hands together, and repeatedly, for that neuron-activating performance.’

Among those present at the reception were Deborah Bull, King’s College London; Claire Moriarty, Defra; Jack Kreindler of Sentrian; David Rossington of DCMS; Stuart Hobley and David Heathcoat-Amory of the Heritage Lottery Fund; John Owen of Fidelity UK; Stephen Deuchar, Art Fund; actor Toby Jones; TV presenter Dallas Campbell; Mike Muller, ARM Holdings; Alex Papadakis, Papadakis publisher; Dea Birkett, Kids in Museums; Gillian Reynolds of the Telegraph; John Elkington of Volans Ventures; Oliver Morton, Economist; Will Jackson, Engineered Arts; Profs Jon Agar and Arthur Miller of UCL; Rob McCargow of PwC; Paul Hardaker, Institute of Physics; Stephen Breslin, Glasgow Science Centre; Claire Mackintosh of The Orr Mackintosh Foundation; Martin Roth, Director, V&A; Andrew Cohen, BBC; Lucy Rogers, RobotWars; Becky Parker, Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys; Anthony Geffen of Atlantic Productions; Katherine Courtney of the UK Space Agency; Alan Brown, Wellcome Trust; Judy Wajcman of LSE; Ulrich Kernbach, Deutches Museum; Sir Mark Walport, Government Chief Scientist; and Trustees Fiona Woolf, Anton Valk, Sharon Flood, Simon Linnett and Lopa Patel .

The exhibition tells how the story of robots dates back to the emergence of a mechanical view of the heavens, many centuries before the word “robot” (Czech for “serf”) was first coined in the 1920 science fiction play Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots) by the Czech Karel Capek, in which a robot rebellion extinguishes the human race.

Visitors enter by walking past a wall of artificial skulls with robotic eyes, an interactive artwork named Area V5 after the part of the human brain which perceives motion by its developer, Louis-Philippe Demers of Nanyang Technical University, Singapore.

In the exhibition they are first confronted with an animatronic baby, under whose latex skin three dozen metal joints whir. Ben Russell, lead curator, said: ‘Coming face to face with a mechanical human has always been a disconcerting experience. That sense of unease, of something you cannot quite put your finger on, goes to the heart of our long relationship with robots.’

The rise of the mechanical cosmos is represented by several objects, including the oldest astronomical instrument originating in western Europe, an astrolabe made in France in about 1300. This view of the heavens as clockwork, along with a surge of anatomical insights, provoked discussion of the human body as a machine, paving the way for the earliest robots.

Among the first objects is a mechanical crucifixion sculpture constructed in Brittany in about 1700, which would have wept drops of wooden blood while the Virgin Mary stretched out her wooden hands.

Another expression of mechanised faith, an automaton monk – built in around 1560 and one of only three in the world – is on loan from the Smithsonian. Attributed to Gianello Toledo, in Spain, the clockwork figure can walk, move its lips, raise a crucifix and rosary, and beat its breast.

Ian Blatchford singled out some of the more spectacular automata, the Silver Swan lent by the Bowes Museum in County Durham. When Mark Twain saw the swan in 1867 he wrote that it had “a living grace about his movement and a living intelligence in his eyes”. Devised by Belgian horologist John-Joseph Merlin in 1773, the swan will be on display until 23 March.

Blatchford added that the newly reconstructed ‘rose engine’ automaton lathe (German, 1750-1888) was ‘two and a half metres of pure bling that would look at home in President Trump’s drawing room.’

During the next phase of the rise of the robots covered by the exhibition, automated looms and spinning machines would come to replace skilled craftsmen. In Lyon in 1744, Jacques de Vaucanson caused a riot by introducing an automatic loom powered by a donkey.

Maria, the first Hollywood blockbuster humanoid, seen in Fritz Lang’s 1927 film, Metropolis, raised yet more troubling questions about the place of humans in a world of machines. Also present in the exhibition is the ultimate dystopian robot, the T-800 used in Terminator Salvation.

Visitors can come face-to-face with Eric, a modern recreation of the UK’s first robot rebuilt as a result of a Kickstarter campaign, as well as Italy’s Cygan, a 1950s entertainment robot which once danced and performed in shows.

The challenges faced by machines attempting to mimic human abilities, such as walking, is also explored, with the intricate mechanisms of the Bipedal Walker – rescued by curator Ben Russell from a forgotten cupboard – and Honda’s P2, two of the first robots to walk like humans.

In an array of Perspex boxes in the penultimate section, visitors can watch the two-armed Swiss robot YuMi make and throw paper airplanes and also interact with several robots: Inhka, a former receptionist at King’s College London, answers questions and offers fashion tips with attitude; Zeno R25 replicates facial expressions; Rob’s Open Source Android (ROSA) tracks visitors; and Pepper invites humans to touch its hands and fist bump.

The android Kodomoroid, the most life-like of its time, reads robot-related news bulletins three times every hour; RoboThespian gives theatrical performances; and Nao, the most ubiquitous humanoid robot, stands (unless ‘tired’, when it sits) to tell a story exploring how robots make decisions.

Later this year Robots will go on tour, visiting the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester to launch the 2017 Manchester Science Festival, the Life Science Centre in Newcastle (2018) and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh (2019), then tour internationally until 2021.

Chair of the Science Museum Group Board of Trustees, Dame Mary Archer told the VIP reception how the Heritage Lottery Fund had “enabled us to create a new robotics collection for the nation and also digitise that collection’.

She thanked the exhibition’s media partner, the Guardian, and also the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council; Federal Department of Foreign Affairs Switzerland; The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation; The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and The Mercers’ Company for helping make the exhibition possible. ‘

Ian Blatchford also contributed his thanks. “We would especially like to thank Rob Knight, Prof Owen Holland, Prof Cynthia Breazeal, Prof Simon Schaffer, Prof Vanessa Toulmin and Prof Alan Winfield. “

‘Countless organisations from across the world agreed to lend us their incredible mechanical creations, making this exhibition possible,’ he added. ‘ We would particularly like to thank Dr Shoichiro Toyoda and Toyota, Honda, Softbank, Miraikan, The Italian Institute of Technology and the Shadow Robot Company here in London. ‘

And he made ‘a special mention’ of the Bowes Museum in County Durham ‘for lending us their exquisitely beautiful Silver Swan.’

The exhibition was also visited today by Edwina Dunn of dunnhumby, Nell Merlino, who created Take Our Daughters to Work Day, and Christiane Amanpour , Chief International Correspondent for CNN, representing The Female Lead, a non-profit project that celebrates women’s achievement, endeavour and diversity.

Two books accompany the exhibition. Robots: The 500-Year Quest to make Machines Human, edited by curator Ben Russell, and The Super-Intelligent High-Tech Robot Book, written by the Science Museum’s Jon Milton and published by Macmillan Children’s Books, is an illustrated guide.

Robots is open daily until 3 September 2017, with late opening until 22.00 each Friday (last entry 21.00) and at Lates on the last Wednesday of each month. Admission is £15 adults and £13 concessions, under 7s enter for free (family tickets are available). Tickets can be purchased online or at any ticket desk in the Museum.

One comment on “Robot uprising in the Science Museum”

Comments are closed.

I love Robots they are part of our future hoping to go and see them soon a great idea to have them be part of the science museum