Although this may seem absurd today given our awareness of its health risks, tobacco smoke was once part of an innovative movement in first aid that began to challenge the boundaries of what was considered possible in resuscitation.

A ‘Stimulating’ Resuscitation Kit

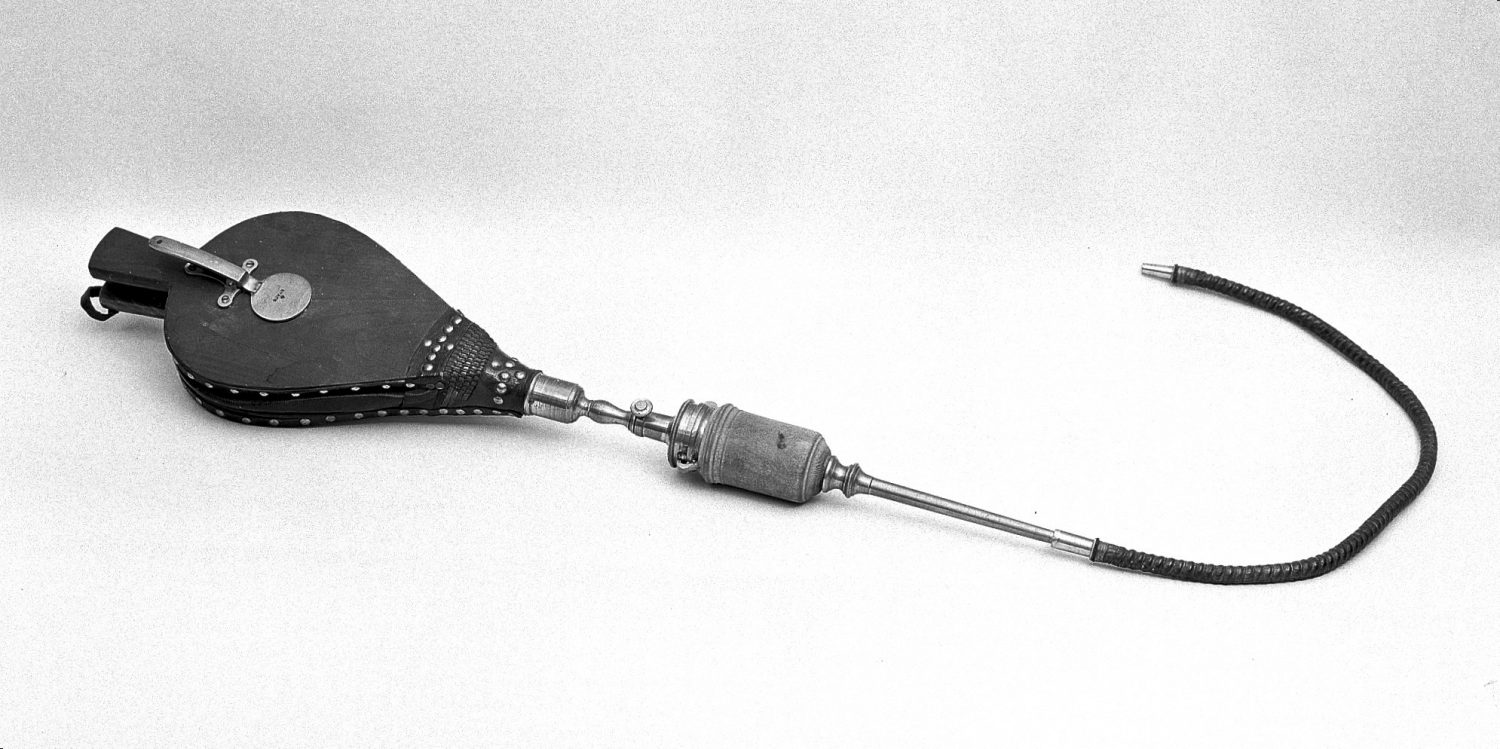

Complete with a set of bellows and fumigator, this medical toolkit does not immediately scream ‘resuscitation’ to twenty-first century observers. And yet in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, this kit was one of many distributed along the River Thames to be used to revive people who had recently drowned. It includes a set of bellows, a fumigator, an ivory syringe, and a variety of tubes and nozzles that could be inserted into various…bodily orifices.

This resuscitation kit embodies many of the ideas that were being debated at the time, some of which may be more familiar than others. A great deal of thought was put into different ways water could be expelled and the lungs inflated. Mouth-to-mouth was a recognised technique but fears over the spread of contagion meant that it was generally avoided (it was only from 1959 that it became commonly used).

A pair of bellows, on the other hand, seemed to be a healthier alternative and so they were used to inflate the lungs with ‘atmospheric air’.

However, this was not all the bellows could be used for. Attached to the fumigator, the bellows could also be used to deliver a tobacco smoke ‘clyster’ or enema, quite literally blowing smoke up the patient’s rectum.

At the time, many medical treatments were based on the theory of the four humours, which suggested that good health was ensured by balancing the bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile.

Those who had apparently drowned were thought to suffer from an excess of wet phlegm and cold black bile. Introducing warm and dry substances into the body was therefore considered key to resuscitation, leading physicians to use different ‘stimuli’ to encourage the heart to resume beating.

Medicinal ingredients could be administered orally, using the ivory syringe also included in the kit, but tobacco smoke clyster pipes were a particularly popular treatment. The warm, dry vapours produced by burning tobacco and nicotine were thought to encourage the lungs and heart back into action, particularly when directed into the bowels through the rectum. With the occasional smouldering ember accompanying this smoky enema, perhaps ‘stimulating’ is a bit of an understatement.

Reviving Persons Apparently Drowned

You may wince or even laugh at what seems to be an absurd idea, given what we know today. However, at the time, this kit was part of an innovative movement that began to challenge the boundaries of what was considered possible when reviving the apparently dead.

The idea of resuscitation itself was not new, and stories of people apparently dead being restored to life repeatedly emerged throughout the last couple of millennia, the earliest of which include the biblical tales of the prophets Elijah and Elisha. However, these stories were often seen as miracles or phenomena, and it was only from the mid-eighteenth century that physicians, surgeons and apothecaries attempted to push resuscitation into the medical mainstream, inspiring a flurry of research and experimentation.

In cities across Europe, societies dedicated to the rescue and revival of the apparently drowned sprung into existence, starting with Amsterdam in 1767. Reports of their successes later reached England, and in 1774, William Hawes (an apothecary) and Thomas Cogan (a physician) founded the ‘Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned’.

Later becoming the Royal Humane Society, this initial group of thirty-four volunteers purchased lifeboats and equipment for rescuing the drowning, published manuals for reviving these ‘unfortunates’, and created receiving houses where the drowned could recover. They also created these resuscitation kits and deposited them along the Thames, making sure the necessary equipment was available and portable in the case of a sudden emergency.

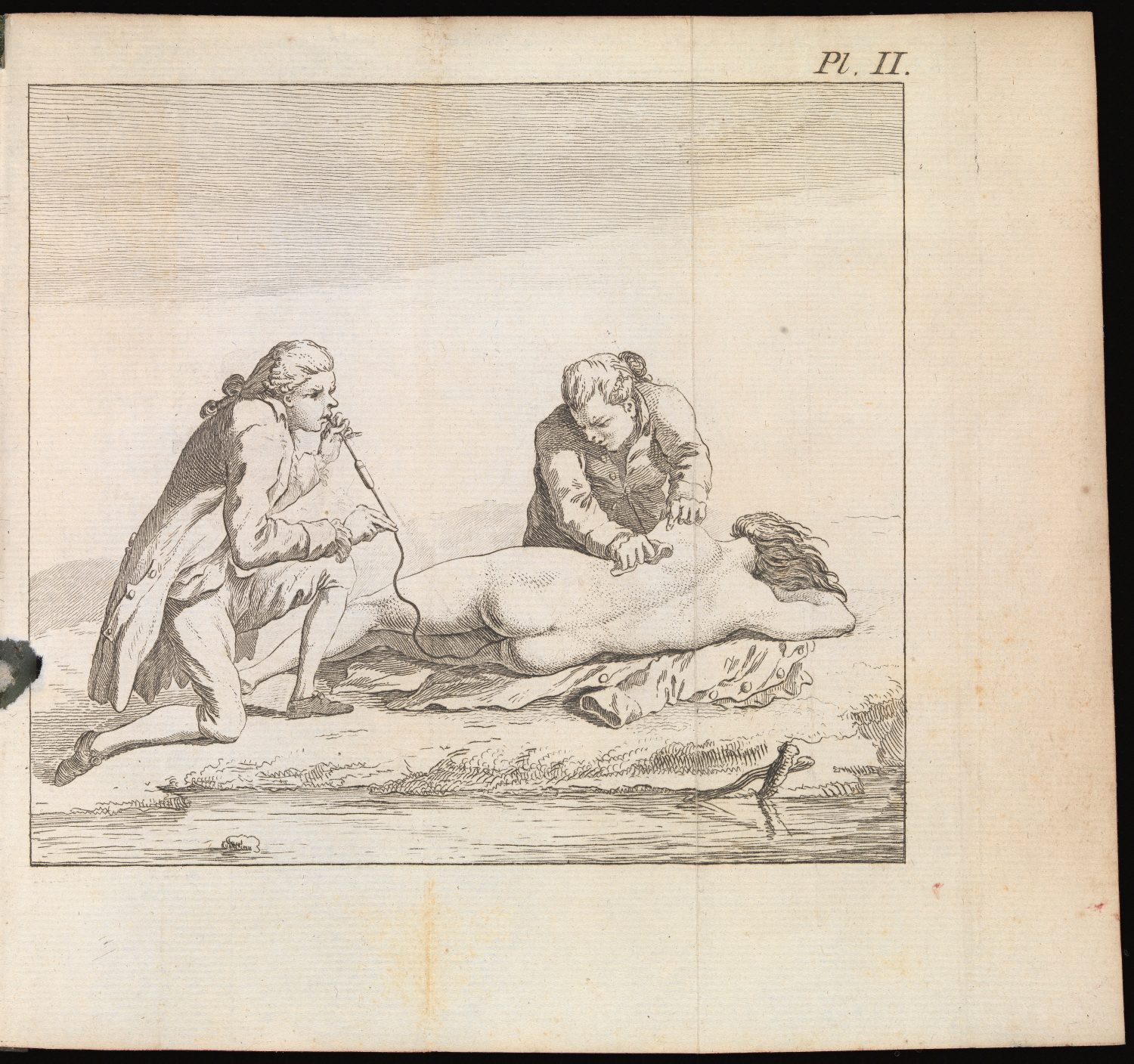

The below paintings were commissioned by the Royal Humane Society. The first depicts a man being rescued from a river, and the second reveals the same man alive and well, having been resuscitated by William Hawes and John Coakley Lettsom (another member of the Society). They were used to advertise the good works of the Society at public dinners, transforming skepticism into generous donations.

Not to be tried at home

It will probably relieve swimmers across Europe that first aid has moved on considerably since this kit was created, and so worry not – it is extremely unlikely that you will ever be treated with this smoky enema.

As early as the 1780s, doubts were being voiced about the effectiveness of tobacco smoke. Later, in 1811, Benjamin Brodie’s experiments on animals revealed that nicotine was toxic, meaning that the days of tobacco enemas were numbered. Similarly, French physician, Leroy d’Etoiles, discovered that artificial respiration using the bellows could in fact rupture the alveoli of the lungs in 1829, and so I wouldn’t recommend adding a set to your personal first aid kit.

No matter how outdated and bizarre this kit may seem, however, the intent behind their creation set the ball rolling, leading to new (and more effective) techniques. After all, humane societies encouraged us to seriously challenge what was considered possible, and to think up new solutions to the problem of bringing people back from the brink of death.

You can see the resuscitation kit on display in Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries.