The first scrambler phones were invented prior to the Second World War to secure voice transmission for commercial use. You can think of a scrambler as an encryption device for analogue signals – an analogue signal is a continuously varying, smooth signal, whilst a digital signal has discrete values.

Standard digital encryption works by applying mathematical functions to the digital data to produce codes. Scrambling works by taking an analogue waveform and modifying the frequencies in a way that makes it incomprehensible. The wave is then unscrambled, a process that transforms the wave back to its original form.

Secraphone

This scrambler phone, which later became known as the Secraphone, was developed in the UK in the late 1930s by the General Post Office (GPO).

The Secraphone consists of two parts. Firstly, the scrambler – originally called a frequency changer – constructed using valve technology. The second part was a handset which, traditionally for scrambler phones, had a green or lime green handpiece. The handset was based on a standard handset in use at the time and was normally placed on a desk with the scrambler under the desk or in a different room.

To operate the phone, the call was initiated in the normal way. In the case of the Secraphone, which had no dialling capability, this would have been through a switchboard operator. Once the call was set up, both parties pressed their ‘Secret’ button. Anyone listening in on the line would now hear unintelligible noise.

If the switchboard operator tried to attract the attention of the Secraphone callers, they would hear the operator as unintelligible and would need to press their ‘Engage For Secret’ button to hear the operator while holding the secret call.

The scrambler worked using a technique known as ‘Frequency Domain Scrambling’. Essentially, the telephone signal was inverted around a chosen frequency, so that the high frequencies become low and vice versa.

However, this type of scrambler was really only secure against the casual eavesdropper such as a telephone engineer or switchboard operator. It was easy to break as it was only necessary to find the inversion frequency and re-invert to unscramble the signal.

In fact, the frequencies were not changed much by inversion so that an experienced listener was often able to get a sense of the message without unscrambling.

The scrambler was used by Winston Churchill during the early part of the Second World War to communicate with the government and the military.

The Bell Labs A-3 Scrambler

In the early 1940s, a scrambling system known as the Bell Labs A-3 scrambler was used in transatlantic communications including those between Churchill and Franklin D Roosevelt, President of the United States, during the Second World War.

The A-3 used the same technology as the Secraphone but was more complex with the signal being split into 5 bands, each of which could be plain or inverted every 15-20 seconds.

Unfortunately, at least one German engineer had worked at Bell Labs before the war and was, therefore, able to develop equipment that could decode the conversations in real-time.

Both the US and Britain were aware that calls were being monitored by the enemy and introduced a system of censorship. Before each call, a censor would explain the ‘rules’ of the call to both parties and make a shorthand transcription of the call. At the same time, the censor would listen for any potential breaches of security regulations such as military details, food supplies, bomb damage, and immediately disconnect the call.

Ruth Ive was a telephone operator and acted as one of the censors for Churchill’s calls. In her book ‘The Woman who censored Churchill’ she recalls how she had to disconnect one of Churchill’s calls as he was about to describe a daytime V2 rocket attack on a London Street market, resulting in dozens of casualties.

Callers were not allowed to identify themselves by name, however, the German interpreters quickly recognised key callers such as Roosevelt and Churchill, even though they referred to themselves as Mr. Smith and Mr. White.

Although the Allies were able to break German text encryption systems, such as Enigma, and had superior text encryption systems that were not broken by the Germans, the opposite is true for voice communications where the Germans were superior. From the autumn of 1941 to July 1943, when a new scrambler system known as SIGSALY was introduced, the Germans were able to intercept, decrypt and listen to almost every word spoken through the A3 encryption system.

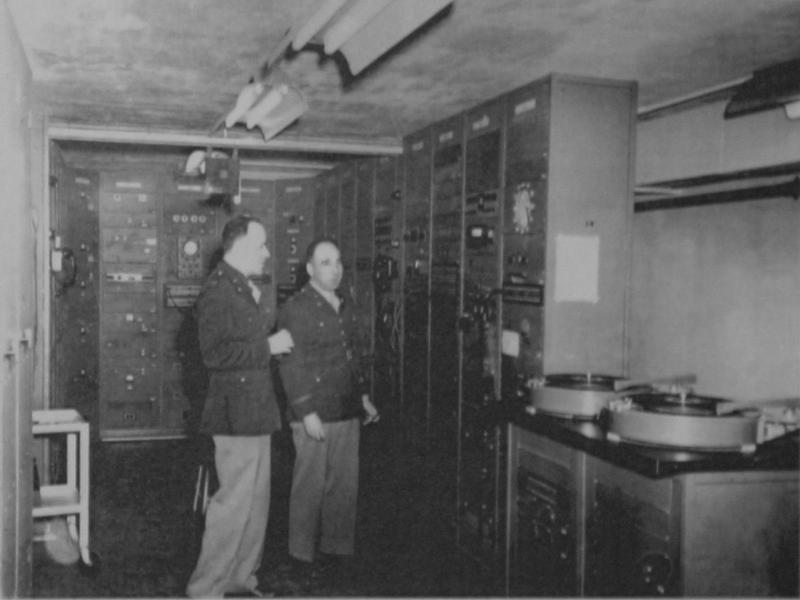

SIGSALY

SIGSALY (the word is made up rather than an acronym) was also known as ‘The Green Hornet’ because of the buzzing sound of the signal. It was developed by Bell Labs and introduced in 1943 for scrambling the highest levels of secure communication. Alan Turing was also involved in the design, validating the security of the system.

SIGSALY worked by first digitising the speech signal and then encrypting the signal by adding in a digitised random noise signal which acted as a key. The random noise was generated using electronic valves and stored on a phonograph record.

Each record was duplicated – one for each end of the conversation – and was capable of holding 12 minutes of noise or key information. The system also included a synchroniser to ensure that both ends of the system remained in synchronisation.

SIGSALY was based on valve technology and was huge – weighing 55 tons, taking up 2500 square feet of space and requiring 30,000 watts of power. Because of the enormous amount of heat generated, air conditioning was required. It was far too bulky to be stored anywhere in Whitehall and was, therefore, situated in the basement of Selfridges.

SIGSALY technology employed many technological ‘firsts’ and was in operation until 1946. During this time, there is no record of any conversations being broken.

This was originally posted in support of our Top Secret: From Ciphers to Cyber Security exhibition that was open from 10 July 2019 – 23 February 2020.