As a new exhibition on James Lovelock opens, his daughter Christine recalls her science-filled childhood and the night they sat up waiting for a comet to destroy the Earth.

When I was a child my father took us to the Science Museum in London. His favourite exhibit was the Newcomen steam engine, built in the early 18th century to pump water from mines. He told us how much the museum had inspired him when he was a child. Science had become the abiding passion of his life, and as we grew up it was the background to ours as well.

We lived for a while at the Common Cold Research Unit, where my father worked, at Harvard Hospital near Salisbury in Wiltshire, and even became part of the research. Whenever we caught a cold the scientists put on parties for us where we would pass on our germs, as well as parcels, to the volunteers who lived in the isolation huts.

My strongest memories of my father during this period are the conversations we had about scientific ideas, whether on country walks or at the dining table. We often had fun working out plots for stories, including one he helped me to write about some fossil hunters on a Dorset beach who stumbled on a fossilised radio set – with shocking implications for the established science of geology.

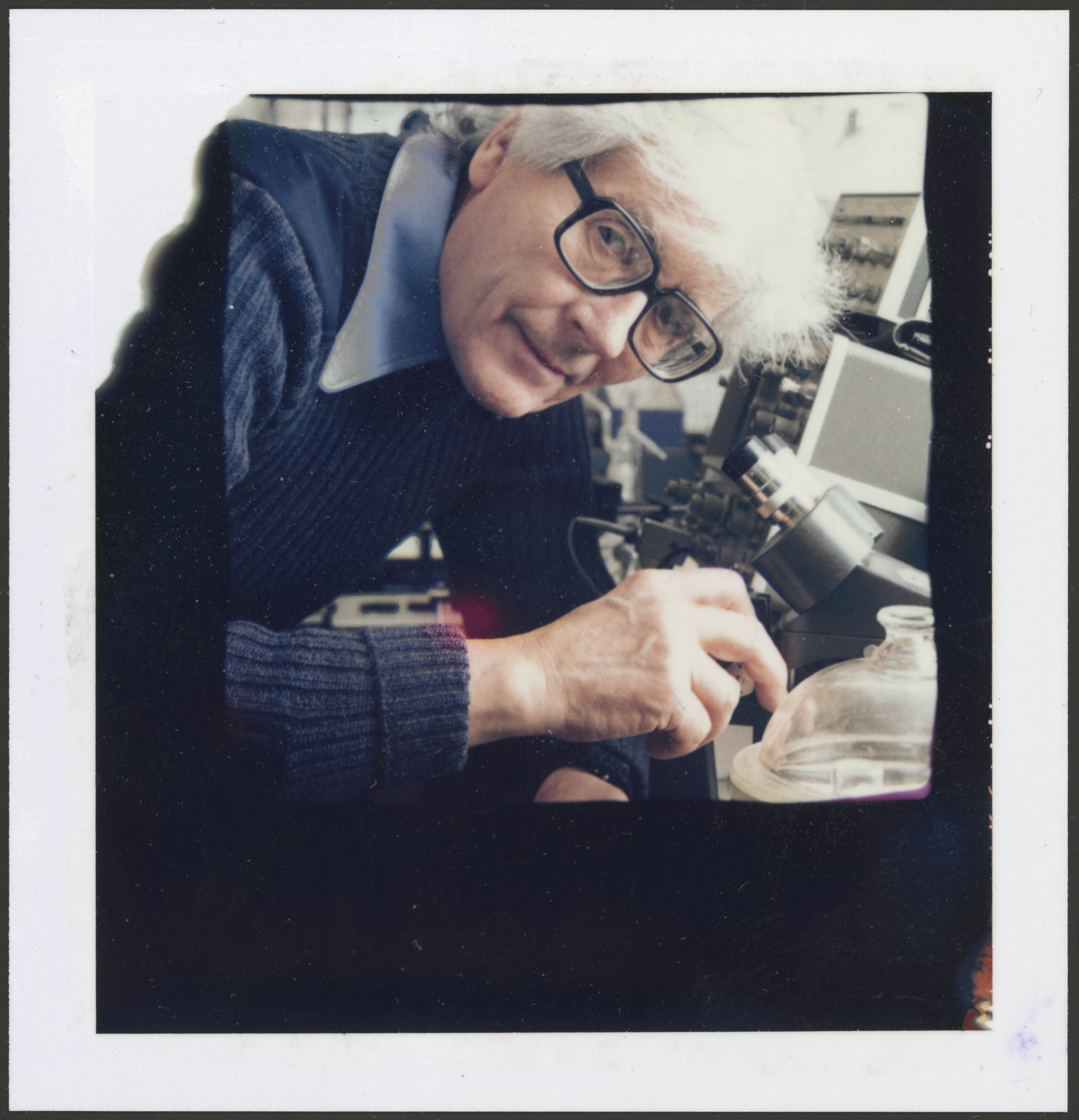

When we moved back to Wiltshire, he turned Clovers Cottage into the world’s only thatched space laboratory. It was full of interesting equipment, much of it home-made, including an electric Bunsen burner. The cottage used to have a skull and crossbones in the window, with the warning “Danger Radioactivity!” My father always said this was a good way to deter burglars.

One evening in the 1960s, my father arrived home from a trip to Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California with some frightening news. A comet had been spotted that was expected to hit Earth that night. The Nasa astronomers back then didn’t have today’s computer technology and said there had been no time to go public with the news.

My father wasn’t worried about the potential disaster. His reaction was a mixture of apprehension, curiosity and excitement. As he said, “If it hits us and it’s the end of the world, we won’t know anything about it, but if there is a near miss, then we might see some amazing fireworks.” While the rest of Britain slept a peaceful sleep, we packed up the car and drove to the highest hill nearby.

I’ll always remember that night, when we snuggled under blankets in the darkness, waiting and watching for what might have been the end of the world. It didn’t happen, of course. The astronomers got it wrong, as my father expected they would, but in an odd – and unscientific – way we felt we had done our bit to keep the Earth safe.

As I grew older I began to help my father more with his work. One day I will never forget is when we went up Hungry Hill on the Beara Peninsula in Ireland in 1969. Our mission was to collect samples of the cleanest air in Europe, blowing straight off the Atlantic. My father then drove straight on to Shannon Airport, and flew with the samples to the United States.

On arrival, a customs officer thought my father was being facetious when he said the flasks contained “fresh Irish air”. An argument ensued in which the official demanded that the flasks be opened, which would have made the whole journey pointless. Fortunately, sense prevailed and the samples reached their destination safely.

Christine Lovelock is an artist who campaigns to preserve the countryside.

You can watch our Youtube video of James Lovelock talking about the inspiration behind his inventions and what the Science Museum means to him.