They call it the Emperor of All Maladies. Half of all people in the UK will be diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime and perhaps it is no wonder that the winner of the prestigious annual Max Perutz science writing award focused on research to defeat the disease which, as people live for longer, has affected ever more people.

Cancer is linked to ageing and marked by a breakdown of cooperation between cells in the body, when one of the body’s many hundreds of cell types develops mutations – spelling mistakes in their DNA – that put the cell’s own interests above the greater good, so they multiply out of control.

Because cancer cells are distorted versions of normal cells in the body, they are hard to distinguish, and then difficult to destroy without causing damaging side effects to normal cells.

While chemotherapy, like surgery, can be effective at initially shrinking tumours, cancer evolves so that tumour cells that survive a treatment go on to multiply, passing on the protective traits that give them that survival edge so they can evolve to resist drugs, or grow faster, for example.

The winning entry to the Medical Research Council Max Perutz Science Writing Award, published last weekend in the Observer, was by Sarah Taylor from the MRC Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, who looked at ‘teaching an old drug new tricks to fight ovarian cancer.’

In her research, Sarah focused on patients whose cancers are much more sensitive to chemotherapy treatment. One reason is that their DNA repair proteins, which are often defective in tumours, allow them to adapt and grow rapidly.

Her hope is to test drugs that block this protein from carrying out DNA damage repair, leaving the cancer powerless, unable to repair the damage inflicted by chemotherapy.

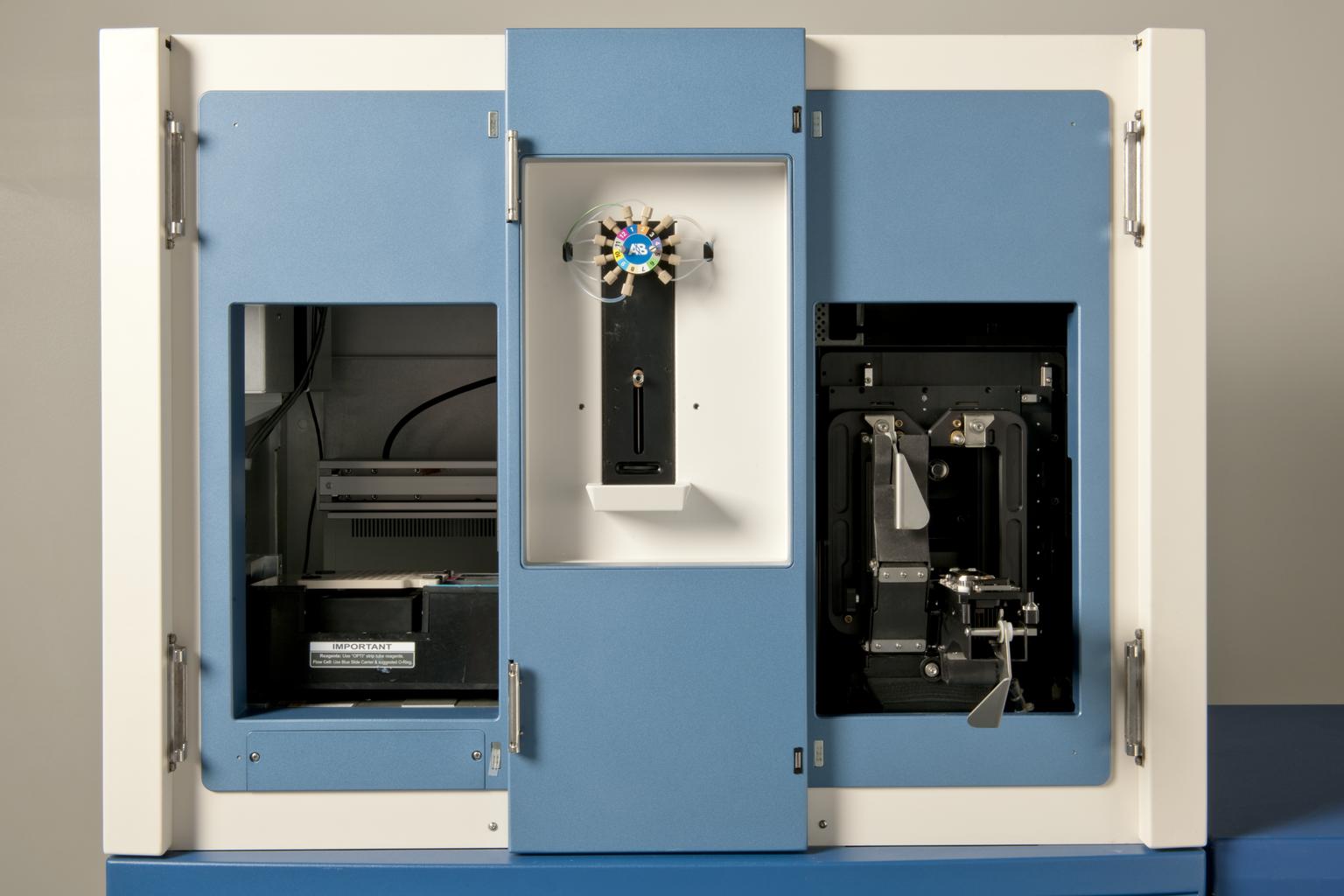

In Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries, you can see pioneering research in this area from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, that led to the development of olaparib, which has transformed the lives of thousands of women with breast and ovarian cancers.

Institute researchers found that targeting a DNA repair protein, called PARP, was a potential way to kill cancer cells, which led to the development of olaparib, and other so-called PARP inhibitors.

As if to underline the importance of cancer research, carried out by the MRC and charities such as Cancer Research UK, two of the ten shortlisted entries also wrote about cancer, breast cancer, the deadliest cancer in women worldwide, with more than two million cases diagnosed globally each year.

Kirsty Balachandran of Imperial College London, is studying the role of the hormone progesterone in breast cancer, which has long been debated.

To provide deeper insights, she treated breast cancer cells with drugs including oestrogen, progesterone and combinations, then studied the genes that go into action in these cells using a method called RNA sequencing. In the process, she generated over four terabytes of data to analyse – the equivalent of 2000 hours of high definition Netflix – to gain deeper understanding of the hormone.

The power of modern genetics to provide new insights into tumours was also underlined by the entry from Isabella Goldsbrough of Imperial College London, who focused on tailoring treatments based on the genetic mutations within a patient’s cancer.

Because cancer is marked by its rapid growth doctors have traditionally used drugs that are toxic to dividing cells but they affect all dividing cells in the body, causing side effects such as hair loss, nausea and so on.

In the long term, treatments based on deeper understanding of cancer genetics – precision medicines, such as olaparib – will increasingly offer an alternative to existing blunderbuss therapies such as chemotherapy.

Runner up for the prize was Julia Wcislo of the University of Dundee, who described her efforts to hunt the hiding places in the body of Trypanosoma cruzi, the parasite that causes Chagas disease.

For her work she tagged the parasites with a fluorescent protein, so they emit a bright green light when bathed in UV-blue light, and could reveal their hiding places using a method to make organs transparent, called tissue clearing.

Three shortlisted entries were commended:

Miranda Buckle, MRC Doctoral Training Partnership, University of Oxford, who described how EEG was being used to detect the brain activity of babies to tell if they were in pain.

Maria Stavrou, of the University of Edinburgh, who is growing healthy cells from the central nervous system – called astrocytes – with human motor neurons to compare them when grown with astrocytes from patients with motor neuron disease.

Fernanda Subtil of the Francis Crick Institute in London was commended for her article which focused on TB and the quest to find the mechanisms of resistance, so as to develop more effective antibiotics. This subject is explored in Superbugs, a Science Museum exhibition which has been touring worldwide.

Also shortlisted were:

Elisabeth Trinh of the MRC Doctoral Training Partnership, University of Manchester, looked at the use of a special kind of gold, called ‘colloidal gold,’ to speed the detection of antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Jonathan Lewis of the MRC Versus Arthritis Centre for Musculoskeletal Ageing Research, University of Birmingham, who is studying bone-producing osteoblasts, and bone-degrading osteoclasts, to find ways to curb bone loss in diseases like osteoporosis, or caused, for example, by low gravity conditions;

Stepheni Uh, of the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, University of Cambridge, who is using a form of artificial intelligence, called machine learning, to provide deeper understanding of young people who self-harm.

With my fellow judges Prof Fiona Watt, MRC Executive Chair, broadcaster and writer Samira Ahmed, Andy Ridgway, Senior Lecturer in Science Communication at the University of the West of England, and the Observer’s Ian Tucker, it was an honour and pleasure to judge a record breaking 140 entries, which provided us a vivid snapshot of medical research and of a new generation of science communicators.

Previous winners have gone on to win national science writing awards, give TED talks and become BBC presenters.

The Max Perutz Science Writing Award competition is supported by the Association of British Science Writers (ABSW) and named after Max Perutz, the distinguished essayist who determined the molecular structure of the blood pigment haemoglobin and helped set up Britain’s ‘Nobel Prize factory’, the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, where research is under way to study COVID-19, among other things.

At the online awards ceremony, he was represented by his son, Prof Robin Perutz. At an event earlier this month, the Science Museum celebrated the life of Max Perutz and other pioneers of structural biology.