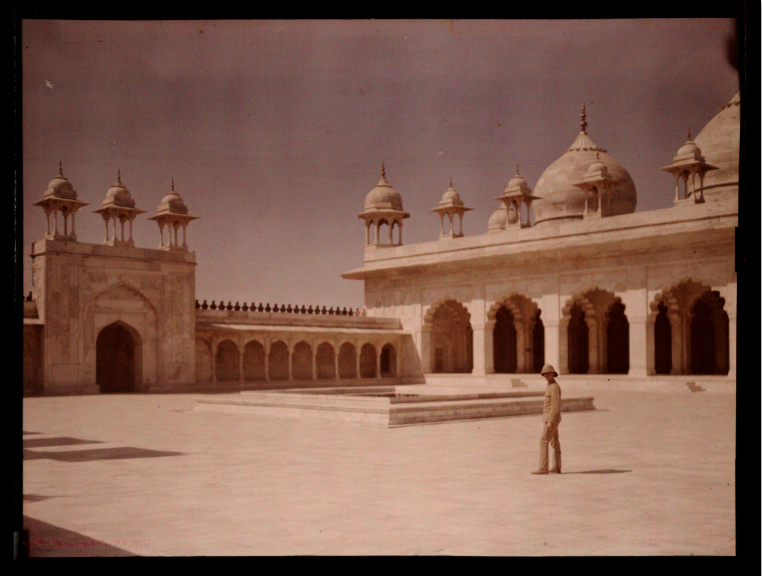

A city devoid of its people is like an entombed spirit, a haunting of memories buried underwood, waiting to be invoked. Like a shrouded voice from gossamer prints of the 19th century blurring into focus, Illuminating India’s opening room is an unearthing of overlapping voices, undetected stories and mired histories, given fresh lease, arising from the earliest days of photography in the subcontinent. It’s rise and transition is punctuated here through freewheeling associations, which chart an alternative arc – sites and the inhabitants claiming equal ground in the display, positioning the viewer en medias res – a point from which to enter both past and present perspectives while also observing the transformation of photo-processes and practices over time. On the occasion of India’s 70th anniversary as an independent nation, such a venture comments on the medium’s restless gait and abundance, its rise to occasion, challenges and assimilations over time.

The curatorial effort to ascertain works of local practitioners from the 19th century is a conscious departure from most previous thematic constellations, which have thus far usually privileged the output of itinerant European photographers. The general intent was to highlight practices of portraiture, landscape and survey imagery, which speak of a dialogue about India as a shared space of mutuality, with voices on both sides clashing and claiming their place – from the colonial to the present. My involvement with the exhibition as Consulting Curator, was then to convey shifts or gaps in the projected history and Orientalist ideology, with aspects that interplayed with the contemporary – whether in terms of media strategy or social relevance. With the hand-painted photograph for instance, it was to scrutinize historical or generational continuity in regional art traditions, hybrid forms as bold gestures of self-expression, while works of performative/self-portraiture (Ram Singh II, Shahpoor N. Bhedwar, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil etc.) could problematize the contemporaneity of current practices by volunteering historical samples that can be regarded as social breakthroughs even today.

Ahmed Ali Khan (active c. 1850-1862) or Chote Miyan (‘Little Master’) in the court of Wajid Ali Shah from Lucknow, represents the early camera work in the midst of a strong courtly culture. Identified as one of India’s first recognized practitioners, documenting one of the earliest female courtesans, Nawab Raj Begum Sahiba, staring causally into the lens, his work suggests how place, privilege and access were crucial variables in representation – who was producing and for whom. As a result, the timeline of the exhibition, 1857-2017, broadcasts discussions on the convivial space of the studio, as well as aspects of coercion, one in which people were persecuted, and even typified as objects of science. And here perhaps the setting of the exhibition at the Science Museum is a potent reminder of postcolonial scholarship around ‘viewing’, given colonial photographs were originally stored here as objects of study, which will now move across to join the colonial and modern photo-collections of the V&A.

The works of William Johnson (active c. 1852-1865) and Vidal Portman (c.1860-1935), both of whom function as veiled anthropologists, express an imperial gaze, closely documenting what were then termed as ‘primitive’ tribes, as well as castes and races, marking ongoing concerns about how naming or denying agency to marginalized communities in the present, can be traced to such visual antecedents. They provide, at times, an eerily playful (photo-montaged people and backdrops), yet searing commentary on heated discussions and activism, which involve the adivasi and dalit communities – the overt and subtle coercion of the disenfranchised subject. And by bringing in Vidal’s work from the Andamans, the exhibition also intimates an India beyond its immediate borders, alluding to a larger S. Asian geography for photography, which may yet be explored in another exhibition (or in continuation to the Whitechapel Gallery show in 2010, Where Three Dreams Cross).

The exhibition however forcefully conveys that the history of photography in India is gradually being unearthed and hence requires constant revision – not as a survey of what exists (which is impossible) but samples which highlight a shifting focus and insinuate broader fields of investigation. Its developments are not only linear, and hence the interest in schools and styles of depiction are also focused on. Though we do not see early Indian women photographers from India (from Bengal for instance), the newly discovered, evocative works of Helen Messinger Murdoch (1862-1956), are an intriguing example of a woman photographer in India at the turn of the century, experimenting with the Autochrome colour process which predates the Kodachrome technique that became popular in the 1930s. The only ones we have seen of late,from India are those from the Albert Kahn collection in France, or others shot by Umrao Singh Sher-Gil (1870-1954), some of whose reproduced, portrait images are also on view.

Room after room, decade after decade, the exhibition deploys time as a sequencing tool, and we see how technology catalyzes and makes possible the imagistic rendering of new ideas, themes and visualizations. In conjunction with some rare images leading to the post-independence photojournalism of Sunil Janah (1918-2012), Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) and Homai Vyarawalla (1913-2012), there is a parallel depiction of notions of ‘modernity’ in other forms such as architecture, looking once again at both Indian and European practitioners – the brick and mortar exultation’s captured by Lucien Hervé (1910-2007), Werner Bischof (1916-1954) and later Madan Mahatta (c.1932-2014). They open out discussions invoking the cultural impact of India on Europe and the impressive international collaborations between practitioners in different fields – be it the study of Hindu temples by Swiss photographer Raymond Bernier (1912-1968) for scholar/curator Stella Kramrisch; or the photographed exhibitions of Bauhaus and German Expressionist luminaries held in India; or the path-breaking work of cinematographer Josef Wirsching (1903-1967) for Bombay Talkies; or the imaging of Indian fashion through the lens of Cecil Beaton (1904-1980).

The complicated terms of location and identity explored in the space-age imagery of Hervé, and his oblique monotone views, cropped frames and abstract compositions, are countered by the bright dynamic colour photography of Mitch Epstein, for instance, who depicts the existential ironies and epiphanies of ‘ordinary’ Indian life. These latter works illuminating public space and the collective experience point towards one of the two trajectories of realism that developed post-Independence: the photojournalism of practitioners such as Raghu Rai and the more personalized, interiorized image spectra of practitioners, such as Ketaki Sheth, Dayanita Singh and Pablo Bartholomew.

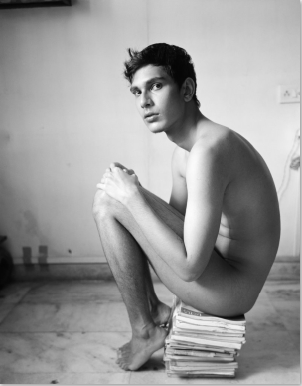

Nationality and nationalisms apart, we come to the contemporary field, where questions of gender, sexuality, personal history and also historical appropriation come into focus as ways of exploring the web of connections one makes with one’s surroundings. Sohrab Hura (Indian), Vasantha Yogananthan (French) and Olivia Arthur (English) are exhibited here scrutinizing broader aspects of mobility and exchange, as well as of transfer, relocation and exile.

Here the exhibition, plausibly and quietly subverts its own title cause by illuminating uncertainties about questions of belonging, representation and agency as well as tracing the infinite connections that may exist in a globalized world where relationships can be fleeting, immediate, intermittent or even ruptured. And perhaps here the exhibition shifts from assertions about image-making to propositions and investigations of spaces that may be private, wherein the individual tells a tale through photography’s poetic potential, suggesting that India’s place in photography’s world is one begging to be retold.

A symposium organised at the Science Museum on the question of ‘place’ and photography suggested some avenues of enquiry. One possible way of devising new dialogues in the future is by continuing to draw aesthetic lines of force back to one’s origins and re-calibrating those into new dimensions – the shaping of a revisionist cartography not merely through a redeployment of traditional imaging of the ‘home-grown’, but through skillful application of new technologies and new media forms that provoke the emergence of new testimonies of oneself and one’s ‘other/s’.

Illuminating India: Photography 1857-2017 is part of the Science Museum’s Illuminating India season, which also comprises Illuminating India: 5000 Years of Science and Innovation and a series of events. Both exhibitions will run until 31 March 2018.