In the 1930s, as the German air force grew in strength, the fear of air attack became intense. Prime Minister Baldwin had warned that ‘the bomber would always get through’, but a minority, including Winston Churchill and his scientific adviser, Frederick Lindemann, argued that some new form of technical defence must be possible. Surely Britain’s scientists – affectionately known as boffins – could devise a countermeasure?

In February 1935, a pilot from the flight research establishment, Farnborough, was told to fly a bomber to the Midlands and back. He was not told why, but the course took the aircraft past the BBC’s short-wave transmitter at Daventry.

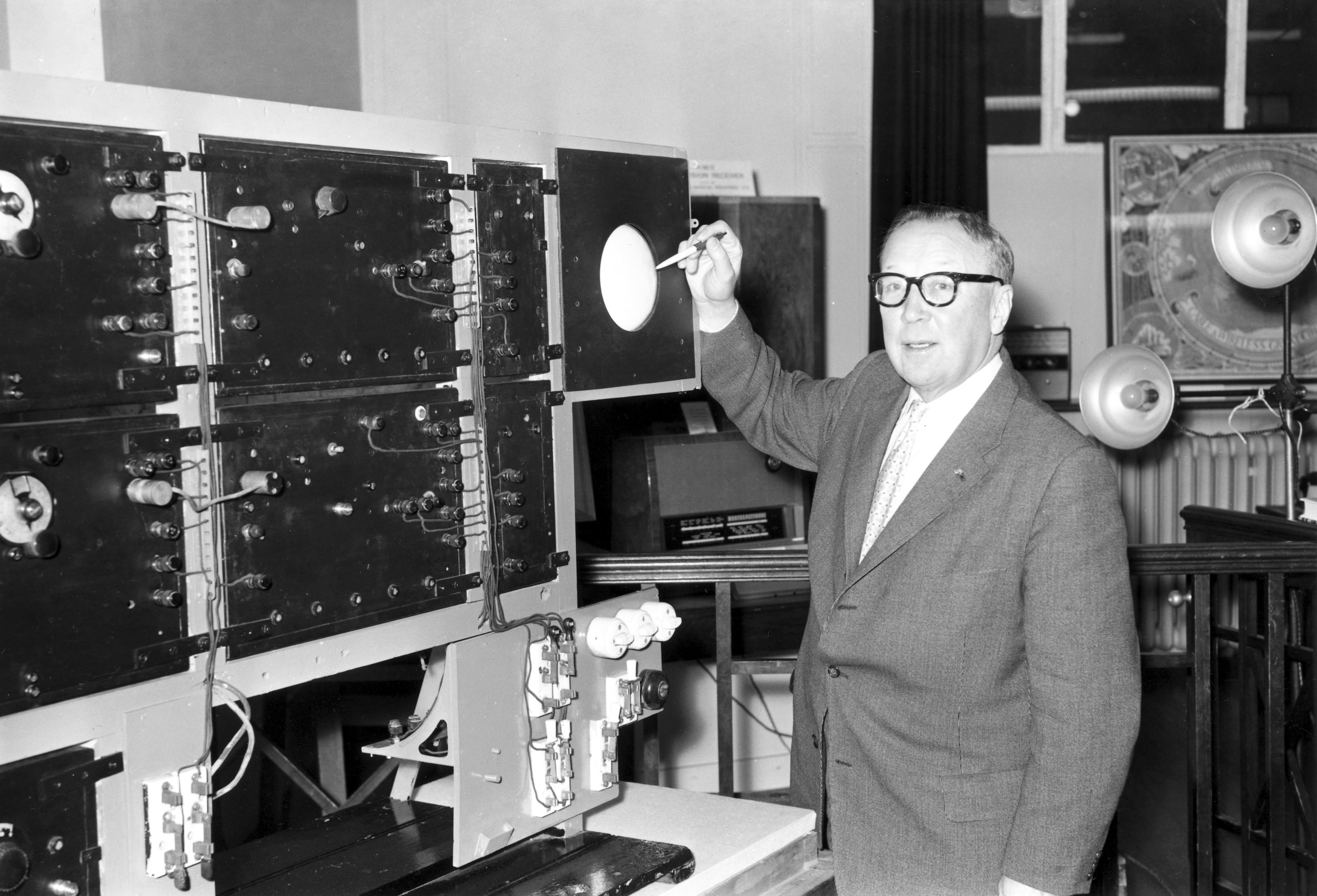

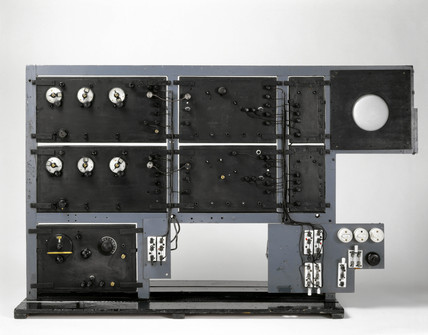

Hunched in a van on the ground nearby, Robert Watson-Watt from the National Physical Laboratory and his colleague, Arnold Wilkins, intently watched a cathode ray tube on a cumbersome radio receiver. They hoped that the powerful BBC signal would be reflected strongly enough from the bomber to be detected. As the aircraft flew past about eight miles away, a green spot on the screen appeared, grew, and shrank away again.

The two men had ‘seen’ the aircraft by its electronic echo. Watson-Watt turned to Wilkins and reputedly said ‘Britain is an island once more’. Following this trial – the Daventry experiment – cash secretly began to pour into developing radar technology. Research took off at immense speed, first at Orfordness in Suffolk and then nearby at Bawdsey on the mouth of the Deben river. Just a year after the first trial, the detection range had improved to 75 miles and 120 miles was later achieved.

Soon, a series of stations with massive 360 feet (110 m) radar masts began to spring up around the coast until there was an unbroken chain watching out to sea for enemy aircraft called the ‘Chain Home’. This radar system was not, for its time, especially ‘hi-tech’, but it was designed to be built fast. It was incorporated into a comprehensive control system for reporting and plotting raids, for steering RAF fighters to their targets and for directing the air battles of World War II in real time. It was this integrated system that changed the nation’s fortunes in the Battle of Britain.

During radar development, Henry Tizard, the Air Ministry’s most trusted scientist, shared the secret with John Cockcroft who had been first to ‘split the atom’ in Cambridge in 1932. ‘We met at lunch at the Athenaeum and Tizard talked to me about new and secret devices. These would be troublesome and would require a team of nurses. Would we [the Cambridge physicists] come in and act as nursemaids, if and when war broke out?’ That is how it turned out and British radar became closely linked with the nation’s best scientists. This electronic war proved to be a powerful intellectual challenge. The physicist R V Jones, described it as the ‘the best fun I ever had’.

Of course science came to the aid of war in many other fields including nutrition, the production of penicillin and antibiotics, sea warfare and the Bomb. However, this war also helped launch a post-war scientific renaissance in Britain. Returning scientists achieved striking results in the fields of molecular biology, radio astronomy, nerve and brain behaviour and much more.

Watson-Watt’s original radar apparatus will be on display in Churchill’s Scientists until January 2016. The exhibition will look at the triumphs in science during Churchill’s period in power, both in war and in the post-war era.

One comment on “Robert Watson-Watt And The Triumph Of Radar”

Comments are closed.

Fascinating story!