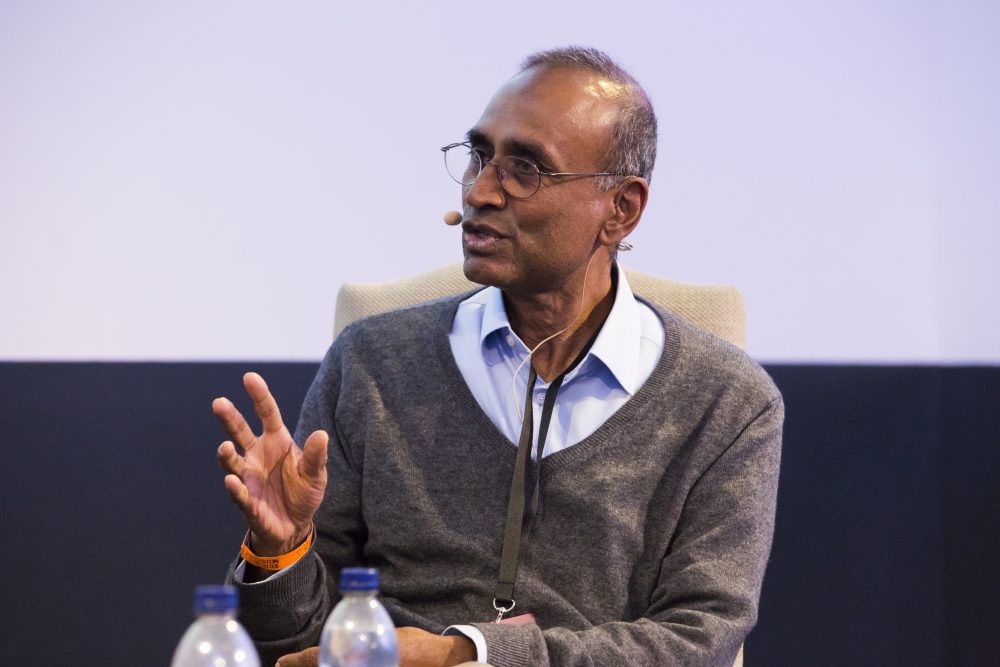

The human face of science and how research is really done, by people with all their talents and foibles, was discussed by the UK’s most senior scientist at a recent Science Museum Lates.

To mark the publication of his book Gene Machine, I talked to Venki Ramakrishnan of the Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology, LMB, and President of the Royal Society.

In 2009 Venki shared the Nobel Prize for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome, which turns genes into flesh and blood, a molecular machine which has evolved since the dawn of primordial life four billion years ago, when the instructions that govern the workings of the living world were written in the genetic material RNA, not DNA.

Ribosomes are huge molecules consisting of a blend of ancient RNA machinery and protein that are at work in all living things today, creating proteins that build and operate cells: some catalyse chemical reactions, others send signals, act as hormones, squeeze muscles and much more.

His book tells the story of his origins in a girls’ Catholic school in Gujarat, India, and gives an insider’s view of the decades-long race between him and his rivals to discern the structure: Profs Ada Yonath in Germany and Israel, Thomas Steitz and Peter Moore at Yale University, and Harry Noller at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The aim of the race was to map the million atoms in this ancient molecular machine to fathom the fundamentals of life, to provide new insights for the development of antibiotics, and claim a share of the Nobel Prize.

If this work were to be done today, said Venki, scientists would use an alternative to X-ray crystallography, called cryo-electron microscopy, which last year won Richard Henderson the Nobel Prize, underlining how Britain’s LMB is a veritable Nobel prize factory.

We met just a few days before the latest crop of Nobel Prizes and it became clear that Venki is uneasy about their corrupting influence. Moreover, when it comes to a Nobel, it can only be shared by three people, when modern science is a cooperative venture relying on much greater numbers of people.

In his book, it emerges that his wife, Vera, was nonplussed too. When she heard that Venki had won the Nobel Prize, she remarked: ‘I thought you had to be really smart to win one of those.’

The foreword of Gene Machine is written by Jennifer Doudna, the University of California Berkeley professor who helped develop the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9, which has transformed research in molecular biology (one use, in understanding details of human development, is described here).

She remarks that Venki Ramakrishnan’s perspectives are unique in various ways, as an immigrant to America and later to England, and as a physicist entering the world of biology. Gene Machine covers professional dilemmas, the serendipity of discovery and the ‘deeply human nature of research’, she says, to give a ‘fresh take’ on the process of discovery.